On Apr. 16, Japanese lawmakers debated whether AI-generated Studio Ghibli images should be banned due to copyright infringement.

For the past few weeks, social media has been flooded with Studio Ghibli-style “art.” From personal photos to well-known fictional characters and memes, countless pictures have been transformed to appear as if transported into the world of Studio Ghibli. It’s hard to escape it wherever you scroll.

These images have been generated with the use of OpenAI after the organization launched an upgrade for its image-generation tools. By uploading a picture and simply typing “convert to Studio Ghibli,” the system will produce the desired image within minutes.

The viral trend had alarmed Japan’s court systems and was the central focus of a House of Representatives Cabinet Committee meeting. They discussed the validity of illegalizing the trend of violating copyright law.

Hirohika Nakahara, the Director-General for Japan’s Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology Strategy, explained, “If it is only a matter of the style or ideas being similar, then it would not be considered copyright infringement. If AI-generated content is determined to be similar to or reliant on preexisting copyrighted works, then there is a possibility that it could constitute copyright infringement.”

In other words, if the artwork only looks like the style of Studio Ghibli, then it is not breaching any of Japan’s copyright laws. However, if the images are identified to be Studio Ghibli-style or are generated based on Studio Ghibli’s works, then it is considered infringement.

Though the generated images are extremely similar, Japanese courts have yet to decide what steps to take against OpenAI’s practice as of now.

Studio Ghibli, a Japanese animation film studio, was founded in 1985 by directors and animators Miyazaki Hayao and Takahata Isao and producer Suzuki Toshio. The studio is famous for its hand-drawn animation that has produced beloved classics such as My Neighbor Totoro (1988) and Spirited Away (2001). With its memorable messages and timeless takes, the studio has won dozens of awards over the years since its first release, Castle in the Sky (1986).

Miyazaki has long made his stance on AI’s involvement in animation clear. In a 2016 documentary called Never-Ending Man: Hayao Miyazaki, a group of developers presented Miyazaki with an animation of a zombie that was AI-generated. The developers had stated that AI can help design movements that were once unthinkable.

Miyazaki, on the other hand, was repulsed by the idea. “Whoever creates this stuff has no idea what pain is whatsoever. I would never wish to incorporate this technology into my work at all. I strongly feel that this is an insult to life itself.”

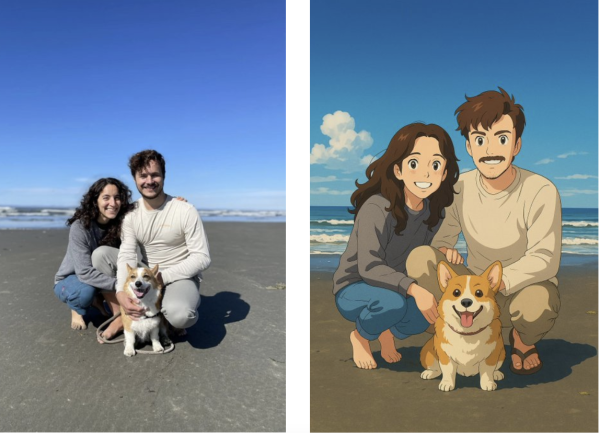

This trend didn’t just start out of nowhere. The idea to combine Studio Ghibli and AI was popularized by a photo of a man, his wife, and his dog.

On Mar. 25, a little after the OpenAI upgrade, software engineer Grant Slatton posted a picture of his family “Ghiblified” on the beach. His post on social media platform X enticed the nearly 52 million viewers to try it out for themselves, leading to the “Ghiblification” takeover.

Slatton even personally generated over 100 images for those who did not have access to the program, demonstrating the power of the frenzy that has captured the hearts of millions.

The “Ghiblification” situation has reminded the world of the questionable ethical use of AI generators and its potential threat to artists once again.

For some, AI generators provide an easy and affordable way to make one’s imagination come alive. For others, a catastrophe to their livelihoods and the catalyst for headaches over determining if a lawsuit is plausible over copyright.

As society debates over the significance of consent for AI images imitating familiar styles, it is unclear where the future of human creativity stands, if there is even a future at all.